If you’ve ever stared at a food label and wondered, “Is this actually good for me?”—you’re not alone. The debate around ultra-processed foods (UPFs) has been heating up, and for good reason. These foods have been linked to weight gain, poor gut health, and chronic diseases. On social media, I have seen more and more people blanket banning UPF’s from their diet, opting to consume only the non-UPF varieties. But here’s the problem: Not all processed foods are created equal, and sometimes? The non-UPF version is actually worse for our health.

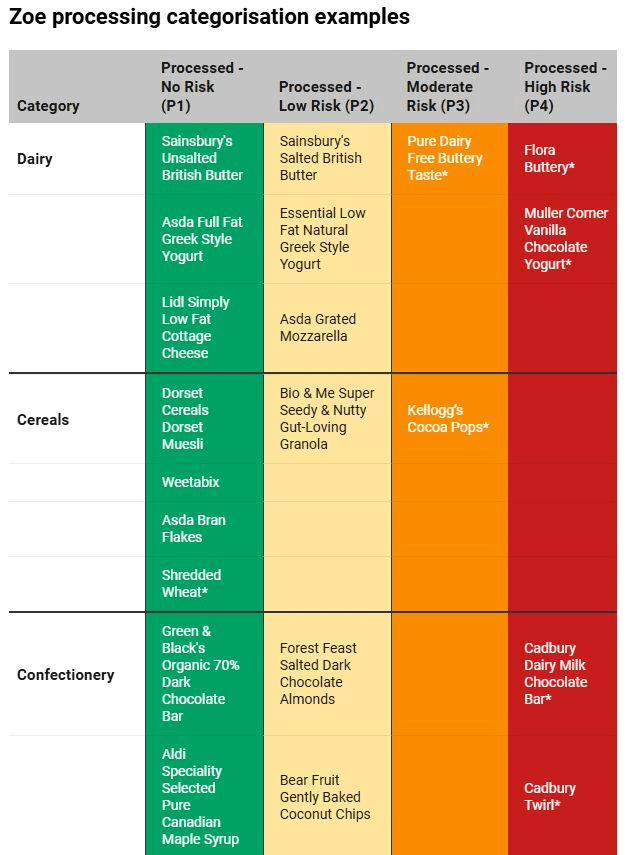

That’s why ZOE—the personalised nutrition company co-founded by Tim Spector—has introduced a new way to classify ultra-processed foods, one that goes beyond the traditional NOVA scale. As a dietitian, I find this approach refreshing—because it’s not about black-and-white rules, but about making smarter, more nuanced choices.

What’s Wrong with the NOVA Scale?

First, let’s talk about NOVA, the most widely used system for categorising processed foods. It splits foods into four groups:

- Unprocessed or minimally processed (e.g., fresh fruits, vegetables, nuts).

- Processed culinary ingredients (e.g., olive oil, butter, salt).

- Processed foods (e.g., tinned beans, cheese, fresh bread).

- Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) (e.g., fizzy drinks, crisps, packaged snacks).

The NOVA system has been groundbreaking, but it has two big limitations: It lumps all UPFs together, whether it’s a sugary cereal or a protein bar made with simple, high-quality ingredients, and it doesn’t account for the fact that some of the non-UPF foods can also be bad for your health in easy-to-consume quantities (butter, anyone?).

This “all UPFs are bad and all non-UPF’s are good” mentality can be misleading—because some processed foods can still be part of a healthy diet, and in fact, may provide you with more nutrition than the non-UPF counterpart.

How ZOE’s New Classification Improves Things

ZOE’s approach is different. Instead of treating all UPFs as equally harmful, they consider the nutritional quality and purpose of the food, alongside its hyper-palatability and energy density. . Here’s how they break it down:

1. “Unhealthy” Ultra-Processed Foods

- These are the obvious culprits: sugary cereals, fizzy drinks, processed meats, and packaged snacks loaded with refined sugars, and unhealthy fats.

- They’re designed to be hyper-palatable (aka addictive) and often lack fibre, protein, and nutrients.

- They often contain additives which have been suggested to have negative health outcomes.

2. “Healthy-ish” Ultra-Processed Foods

- These are foods that may be processed but still offer decent nutrition—like wholemeal bread.

- They might contain some additives, but they also provide fibre, protein, or healthy fats, and so can be included within the diet on a more regular basis.

3. “Beneficial” Ultra-Processed Foods

- Surprise—some UPFs can actually support health! Think: fortified plant milks (with B12 and calcium), fermented foods (like certain yoghurts), or protein powders with minimal ingredients.

- These are processed for convenience or shelf life but still align with a nutritious diet, and do not need to be limited.

Why This Matters for Your Health

As a dietitian, I love this approach because it’s realistic. Telling people to avoid all processed foods is impractical—and unnecessary. Instead, ZOE’s classification helps you:

✅ Identify the worst offenders (cutting down on “unhealthy” UPFs can have massive health benefits).

✅ Make better swaps (e.g., choosing a minimally processed protein bar over a chocolate bar).

✅ Avoid food guilt (not all processing is bad—some can be helpful!).

The Things I Still Want to Know

This does seem like a fantastic step forward, but I do still have a few reservations. For example, how were the metrics selected, and how are they weighted? Equally, it’s really difficult to find anything about this online- is this behind a ZOE paywall? If it is, that is slightly disappointing!

How to Use This in Real Life

Here’s my strategy for applying ZOE’s UPF classification to your meals:

- Read Labels with Purpose

- Look beyond the label claims. Check for added sugars, high levels of saturated fat and low levels of fibre content. If the food doesn’t contain these, yet is still processed; it’s probably a healthy choice.

- Example: A shop-bought soup might be processed, but if it’s packed with veggies and pulses (not just salt and additives), it’s a better choice.

2. Prioritise Whole Foods… But Don’t Stress Over Some Processing

- Base your diet on whole foods (fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, pulses), but don’t panic if you rely on convenient, minimally processed options like tinned fish, frozen veggies, or whole-grain crackers.

- Essentially, use nuance. Obviously a cheeseburger and a glass of fortified plant milk are not on the same level as each other!

3. Watch Out for Hyper-Palatable Foods

- If a food is engineered to make you overeat (crisps, biscuits, takeaway), it’s likely in the “unhealthy” UPF category. Limit these where you can.

4. Embrace Helpful Processed Foods

- Some UPFs can fill nutritional gaps—like fortified cereals (if you struggle with iron) or a high-protein shake (if you’re on the go).

The Bottom Line

ZOE’s new UPF classification is a game-changer because it moves us away from fear-mongering and toward practical, science-backed choices. Instead of stressing over whether a food is “processed,” ask:

🔹 Does this add nutritional value to my diet?

🔹 Could I make a healthier swap?

🔹 Is this food designed to keep me eating more than I need?

By thinking this way, you’ll cut through the noise and make better decisions without the guilt. And that’s what healthy eating should be about—balance, not perfection.

What’s your take on UPFs? Have you found any processed foods that surprisingly fit into a healthy diet? Share your thoughts below!