Ultra-processed foods. The buzzword of 2025. There has been a huge focus on UPF over the past year, following the release of Chris Van Tulleken’s book Ultra-Processed People (which is a great read, by the way) in 2023.

This book, and the following media focus on UPF’s has definitely done a lot of good. Online, we see more and more people being aware of UPF’s and aiming to reduce or remove them from their diet, and in my clinics, I have more and more clients asking about UPF’s, what they are and how to avoid them. This is fantastic to see as a dietitian. For too long, people have generally been unaware of the food they are eating and the impact it has on their body. Understanding that UPF’s aren’t just increasing their risk of disease, but are also changing their brain chemistry and increasing cravings and food intake has really resonated with many people, and as a result, their diets are lower now in fat, salt and sugar than they were previously.

However, there is a big problem with UPF’s and the way they are defined. One which, actually, may be reducing the nutritional quality and increasing the risk of nutritional deficiencies across the nation. One which could lead to a health crisis in the UK if more and more people blanket remove UPF’s from their diet without thinking about the nuance of the topic.

Fortification is not a bad thing

Fortification is considered a form of ultra-processing. The addition of iron, B vitamins, folate, zinc, calcium, iodine or vitamin D is enough to automatically consider a product ultra-processed. As a dietitian, this concerns me, as generally the trend I see online (and with my clients) is that if a person is UPF-conscious, they will cut out all UPF’s without thinking about the nutrients they provide and the consequences of not getting enough of these nutrients. They won’t increase the intake of non-UPF foods which include these nutrients; instead, they simply end up with a nutritional deficit and they believe that this is healthier as it isn’t ultra-processed. This couldn’t be further from the truth.

Fortified foods provide a huge amount of the nutrients of concern within the Western diet. The reason these foods were fortified with these nutrients in the first place is because deficiencies of these vitamins and minerals were wide-spread, prevalent and led to significant incidences of deficiency diseases across the UK and beyond. A key example here is iodine.

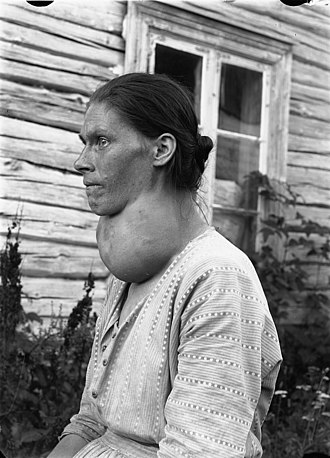

Iodine deficiency was very common within the 1800’s, and commonly caused what is known as a “goitre”, which is the swelling of the thyroid in the neck.

In the UK, the Midlands had a particular prevalence of goitre, to the point where a goitorous neck was known as a “Derbyshire neck”. The photo to the left shows a woman with a Class III goitre, which was caused from a chronic deficiency in iodine, due to severe lack of iodine in the soils of the earth used to grow the crops.

Various countries had endemic iodine deficiencies (>5% total population) caused by this, and each country trialled a different approach to increase iodine consumption. Many, such as the USA and New Zealand, began using iodised salt, which significantly improved iodine consumption and reduced goitre prevalence to near 0. The UK, however, decided to iodise their milk. Washing the cows teats with iodine and providing iodine fortified feeds and injecting the cattle with iodine significantly reduced the amount of goitre in the UK, particularly in the Midlands.

The public health initiative made huge improvements both in the quality of life of the population, but also the intelligence of their offspring; iodine deficiency in pregnancy and early childhood can lead to learning difficulties or disabilities in severe cases.

Now, whilst milk is not considered a UPF, fortified plant milk alternatives definitely are. This is usually because of the fortification within them (but can also be due to the presence of emulsifiers too, depending on the brand). Many manufacturers such as Alpro have listened to dietitian’s concerns regarding lack of iodine fortification in their plant milks, and have begun to fortify their milks with potassium iodide, alongside the calcium carbonate (calcium), cholecalciferol (Vitamin D) and cyanocolbalamin (Vitamin B12). This has greatly improved the consumption of these key nutrients of concern for people who don’t drink regular dairy, and has significantly improved their nutrition and reduced their risk of nutritional deficiency.

However, with the rise in fear mongering of all UPF’s without nuance being added, many vegans or those who are dairy free have been opting for the more “natural” versions of these drinks. These versions often contain only 2 ingredients (soy beans, nuts or oats and water) and have no significant nutrients within them. This is leading to significant nutritional inadequacy and may lead to further increases of deficiency diseases like goitres later down the line.

This raises the question; are all UPF’s really bad?

My take as a dietitian? No. In fact, many foods which are considered UPF are actually better than their non-UPF counterpart because of the fortification. Fortification bears no impact on the taste, texture or mouthfeel of a product. It doesn’t make the product softer or more melting, it doesn’t add any change to the way the product performs, it doesn’t create that perfect trifecta of flavour, texture and mouthfeel which lights up those areas of the brain and make you crave more. Its sole purpose is to add nutrition to the diet and reduce the risk of deficiency.

And it’s not just plant milks which are impacted by this. Cereals, which provide 51-87% of the UK’s RNI for iron and 26-37% of the UK’s RNI for folate every day are affected. Flours and foods made with flour, fortified with various B vitamins and a significant contributor the UK’s consumption of thiamin and niacin, is impacted. The list goes on.

I appreciate what people are trying to do when they aim to remove UPF’s from their diet. I think in many cases, it can improve their nutrition, by reducing the amount of fat, sugar and salt eaten, and reducing the consumption of foods which can lead to cravings. However, the definition of UPF needs to change.

Things should not be simply considered UPF purely because they have fortification added to them. Granted, some of these products which are fortified have other UPF ingredients in them which muddy the water; emulsifiers in plant milks or acidity regulators in breads, for example. But we should look at each of these foods individually, and see whether these foods will be providing us more nutrition and benefit to our health than harm.

ZOE is actually paving the way with this, which is great to see. Whilst I am not generally a big fan of ZOE and the programme they run, I do appreciate that they are trying to add nuance to the discussion. They are categorising UPF’s in 4 categories; no risk, low risk, medium risk and high risk. This adds more nuance to the NOVA classification and stops people from blanket banning UPF’s based off of the irrational belief that non-UPF is always better.

So yes, limit UPF’s. But whilst doing so, be nuanced in your approach. A glass of soy milk is nowhere near the same level of harm as a UPF laden biscuit, cake or piece of fried chicken, and in fact, could be good for your health.