Nasogastric tubes, often referred to as NG tubes, are flexible tubes which are inserted through the nose, down the back of the throat and into the stomach. These tubes are vital for providing a way for dietitian’s to help people get enough nutrition if they are in a state where they cannot swallow safely, for example, if they have dysphagia (a swallowing difficulty), are very fatigued or are in a coma.

While they may seem intimidating, NG tubes play a crucial role in supporting recovery and maintaining nutritional health, and are a vital part of the care and management of malnutrition in a hospital setting.

What is an NG tube?

A nasogastric tube is a thin, flexible tube inserted through the nose, down the throat, and into the stomach. It is typically made from polyurethane or silicone, which are durable materials that won’t be broken down in the acidic environment of the stomach. The tube is secured in place with adhesive tape and can remain in situ for varying lengths of time, depending on the patient’s needs. Generally, however, they are left in place for a maximum of 6 weeks before needing to be replaced, and they are typically only left in situ whilst the person is in hospital (although there are some exceptions to this!)

NG tubes come in different sizes, measured in French units (Fr), with the choice of size depending on the patient’s age, size, and medical requirements. Some tubes have a single lumen (which is the port that things go into the tube via) for feeding or drainage, while others may have multiple lumens for additional functions, such as administering medication.

NG tubes are different to Ryle’s tubes, which are tubes typically used to help drain the stomach of it’s contents if someone has a bowel obstruction. These tubes typically are only used for drainage, and not the administration of feed, fluid or medication.

How does an NG tube work?

Once the tube is correctly positioned in the stomach, it can be used for several purposes. The most common uses include:

- Fluid delivery, whereby bottles of fluid will be drained into the tube to keep hydration levels up. Usually this is only utilised if an NG is already in situ, or if venous access is particularly difficult!

- Nutrition delivery, via what is known as an enteral feed. Enteral feeds are specially designed liquid feeds which contain a specific amount of calories, protein, carbs, fats and micronutrients. These are typically delivered over the course of numerous hours (between 12 and 20 hours is a typical feeding regime), but can be delivered as a bolus, which is a large dosage all at once.

- Medication delivery, which is particularly important for people who cannot swallow pills. This being said, many medications in pill form also have an IV version, and so might not always be necessary.

Why might someone need an NG tube?

There are several reasons why a patient might require an NG tube. Some of the more common reasons include:

- Swallowing difficulties: Patients with conditions such as stroke, motor neurone disease or MS may be unable to eat or drink safely, a condition known as dysphagia. An NG tube ensures they receive adequate nutrition and hydration as it bypasses their unsafe swallow. Some of these conditions can be recovered from, and tube feeding is temporary; others will require a more long-term feeding tube.

- Critical illness or surgery: Patients in intensive care or recovering from major surgery may be unable to eat normally, either due to trauma to their face, neck or stomach, or due to being in a medically induced coma. NG tubes provide a temporary solution until they can resume oral intake. It is typical that as they recover, they will be able to resume normal eating, but there are certain cases where this is not appropriate.

- Gastrointestinal disorders: Conditions like Crohn’s disease, bowel obstructions, gastroparesis or severe nausea and vomiting may necessitate the use of an NG tube for feeding. Some of these conditions may require a slightly different tube to the NG tube, known as an NJ (nasojejunal) tube. These tubes travel further through the digestive system, bypassing the stomach and the first part of the intestine (the duodenum) to end in the jejunum.

- Nutritional support: Patients with malnutrition or those undergoing treatments like chemotherapy, which can affect appetite and prevent adequate nutritional intake, may benefit from NG tube feeding to maintain their nutritional status whilst they are being treated.

There are dangers to an NG tube, however

NG tube feeding isn’t without it’s risks. In fact, NG tube feeding actually forms one of the scenarios found in the NHS’ 16 “never events”, which are situations which should never happen within a healthcare setting. To put it into perspective, some other never events include the amputation of the incorrect limb or removal of the incorrect organ.

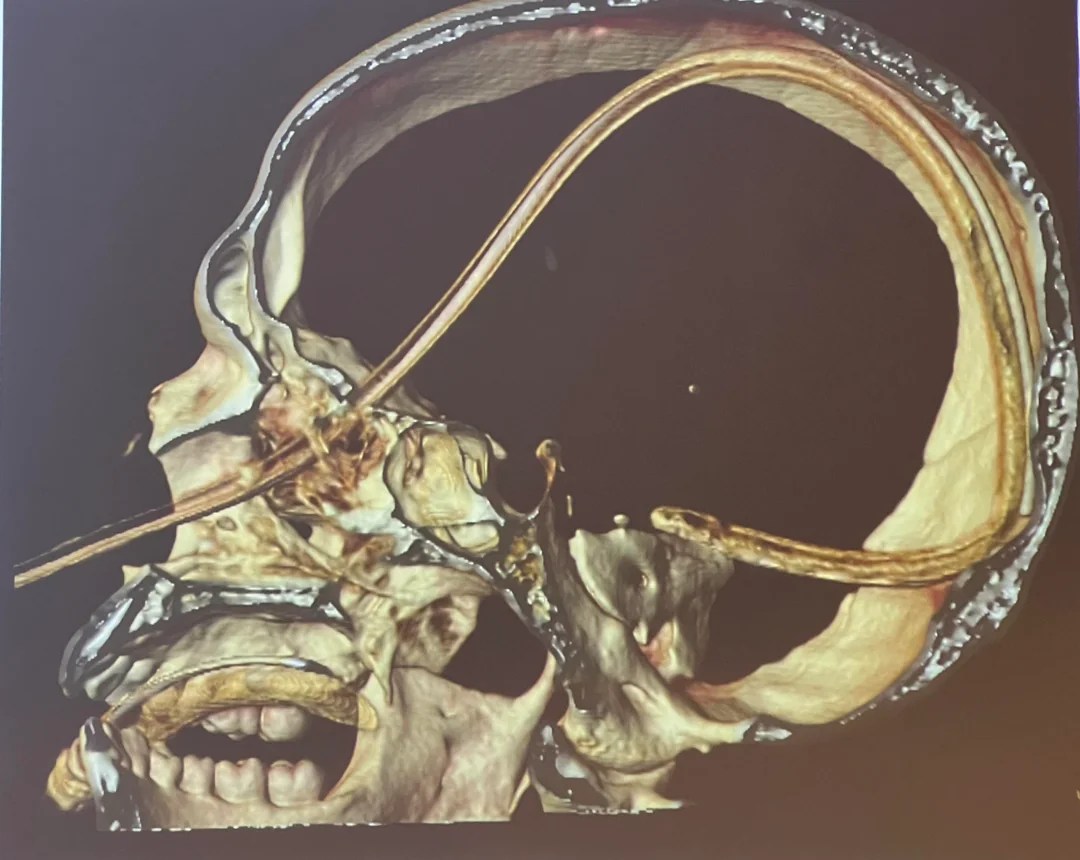

The issue with NG tube feeding (or any other tube feeding which goes up the nose and down the throat), is that there is a high chance that the tube can be misplaced, or become dislodged after it was placed. There are two scenarios where this could occur:

- The NG tube was either inserted into the lung, or became dislodged after placement (via coughing, sneezing or other sudden movements) and has ended up in the lung or above the windpipe.

- The person having the NG tube having a fracture in the base of their skull, and the tube ending up inside the cranial cavity.

Source: Oxford Medical Education

If the feed was administered in either of these situations, there is a severe risk of infection and a high likelihood of death which occurs. Therefore, we need to ensure to check that the tube is positioned properly before administering the feed.

The tubes do have a material within them which does make them visible on an X-ray, and so X-rays can be used to confirm placement. However, often the easiest way to test is to aspirate the tube (which means to pull some liquid out of the tube), and test the pH of the liquid. If the pH is acidic (5.5 or below), that means that it is within the stomach and feeding or fluids can commence. If it is not, then an X-ray should be done to confirm placement, and if the tube is misplaced, it will need to be pulled out and changed.

What do dietitian’s do when it comes to NG feeding?

Whilst dietitian’s can be trained to place and confirm placement of an NG tube, it is more common for us to actually assess the need for the NG tube in the first place, and then work out an NG feeding regime that will be appropriate for the patient.

Assessment

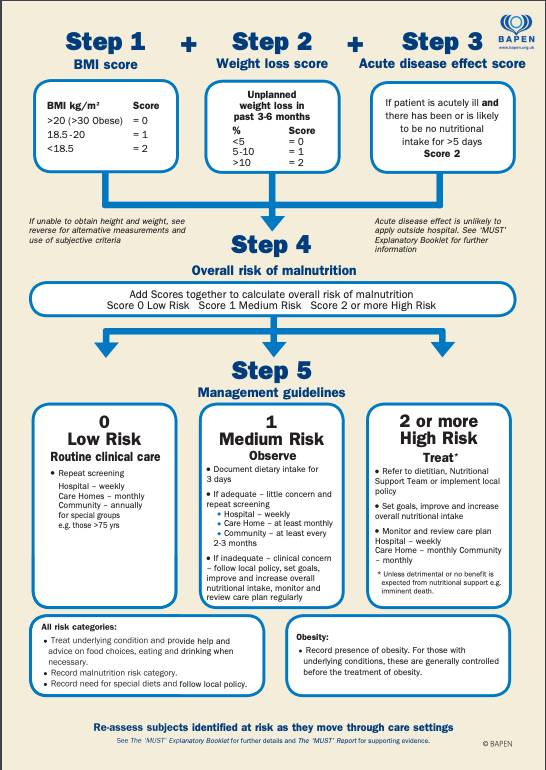

To assess whether an NG tube placement is appropriate, a MUST score must be done first. A MUST score (or Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool) is a standardised assessment done in hospitals to identify those at risk for malnutrition.

Source: BAPEN

For anyone who needs an NG tube, they will automatically score a MUST of 2 irrespective of their weight and BMI, due to the fact that NG tubes are generally only placed if someone cannot or will not be able to eat enough for more than 5 days.

Once this has been ascertained, the dietitian will look at the following:

- Medical history- Why is the person in hospital? Have they ever had any base of skull fractures which would prevent them from being able to have an NG tube? Do they have any medical conditions which would make displacement likely (such as delirium or dementia)?

- Biochemistry- What are their bloods saying? Are there any electrolyte imbalances that will need to be corrected? Is refeeding syndrome likely?

- Dietary History- What is their diet like currently? Are they able to drink or eat well? Has their dietary intake been poor before admission to hospital? Do they have dysphagia?

- Bowels- What are their bowels like? Is it likely they may need additional fibre or fluid to help maintain bowel function?

- Medication- Are there any medications they are taking which could interact with the tube feed, or which could be causing lack of appetite?

This is not a comprehensive list of all of the questions that are asked. There may be other questions which are appropriate to ascertain before identifying whether tube feeding is appropriate.

Ultimately, it is always preferred that we maintain oral intake where we can, as this carries with it far less risk than NG feeding. If the person can eat or drink, it may be more appropriate to encourage oral intake, or to prescribe oral nutritional supplements (ONS) to help sustain their calorie and protein intake. If there are other issues underlying, such as an inability to swallow, extremely poor oral intake despite supplementation, extreme resistance to oral intake, or extreme fatigue (amongst others), then, and only then, will NG tube feeding be considered.

How dietitian’s calculate what someone should be fed

The calculation of a feeding regime is actually more complicated than it first appears.

The dietitian will have to assess the persons caloric, protein and fluid intakes, taking into account their disease state, their activity levels, and any losses which they are experiencing due to their disease state. For example, someone who has experienced significant burns will have significantly higher calorie and protein requirements, to allow for healing of the skin, and will also have significantly higher fluid requirements, as they will be losing a lot of fluid from the burns.

The dietitian will also have to take into consideration the other symptoms the person is experiencing. They may have deranged electrolytes, which need to be adjusted or supplemented for, or loose stools which require some fibre.

Once the general requirements are identified, it is important they take into account if they are getting any of these requirements from other sources. As an example, some medications given to keep people in an induced coma, such as propofol, contain a significant amount of calories which need to be removed from the tube feeding prescription to prevent overfeeding. Equally, the individual may be receiving regular IV’s to correct fluid balance, so this does not need to be given through the NG tube.

The dietitian also needs to consider other medications which have a drug-nutrient interaction. Phenytoin, a commonly prescribed anti-convulsant, can have it’s absorption reduced by 70% if given with a feed. Therefore, someone who requires this medication for seizure control cannot be given a tube feed when the phenytoin is administered. A 1 hour gap before and after phenytoin administration has to be accounted for in the regime.

Once all of this has been considered, the dietitian then needs to find the appropriate feed (as there are many they can choose from!), dosage and flow rate which would work for the patient, alongside the number and dosages of flushes to ensure adequate fluid intake.

People on NG feeds will be monitored every few days to ensure calorie, fluid and protein intakes are still appropriate, and regimes can be adjusted accordingly.

NG tubes can be a lifeline

Nasogastric tubes are a valuable medical tool, providing essential nutrition, medication, and drainage for patients who cannot meet their needs orally. While their use is often temporary, they can significantly impact a patient’s recovery and quality of life. Dietitian’s play a crucial role in assessing the need for an NG tube, ensuring patients receive the right support at the right time. However, like any medical intervention, NG tubes come with potential risks, and their use requires careful monitoring and management.

If you or a loved one is facing the possibility of needing an NG tube, it’s important to have open and honest discussions with your healthcare team. Understanding the process, benefits, and risks can help you make informed decisions and feel more confident in your care.